Tuesday, 23rd April, 2013.

One of the amazing highlights of this tour!

We drove to the section of the wall at Bādálǐng, 70km northwest of Běijīng.

First glimpse of the wall.

“The Great Wall” is a misnomer. It should be called “The Great Steps”.

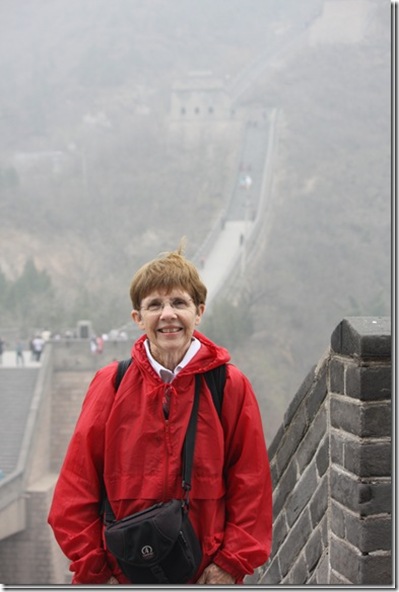

Ahwen explained that we could take the difficult walk to the right or the more difficult one to the left. While some of the more athletic members of our group opted for the more difficult side, we opted for the plain difficult alternative. Here’s a bit of Pat setting out “for upside”.

We checked ourselves out for heart and brain diseases and set off.

Setting off.

The ‘original’ wall was begun more than 2000 years ago during the Qin dynasty (221–207 BC), when China was unified under Emperor Qin Shi Huang (Lonely Planet).

Building the wall required hundreds of thousands of workers – many of whom were political prisoners – and 10 years of hard labour (Lonely Planet).

He who has not climbed the Great Wall is not a true man.

Mao Zedong.

Well, here’s one true man.

Some more “true men”.

Notice how worn the steps are beside the hand rail.

Legend tells that one of the building materials used for the wall was the bones of deceased workers.

Another of my favourite pictures of China.

While the wall occasionally served its impractical purpose of defence, there were some notable failures:

- Bribing sentries was one strategy used by Ghengis Khan’s armies, thus imposing Mongolian rule on China from 1279 to 1368.

- 19th-century European ‘barbarians’ simply arrived by sea.

- By the time the Japanese invaded, the wall had been outflanked by new technologies (such as the aeroplane).

Once the wall was no longer useful for defence, it was largely forgotten.

Mao Zedong encouraged the use of the wall as a source of free building material, a habit that continues unofficially today.

The wall’s earthen core has been pillaged and its bountiful supply of shaped stone stripped from the ramparts for use in building roads, dams and other constructions.

Here are Jan and Dal striding purposefully on ahead of us.

Jan and Dal at the end of the restored “difficult” section.

Jan and Dal.

Us. You can see that after the exertion of climbing, we have now shed our jackets.

On the way down.

The old chestnut that the Great Wall is the one man-made structure visible from the moon was finally brought down to earth in 2003 when China’s first astronaut Yang Liwei failed to spot it from space (Lonely Planet).

Looking through the mist at part of the “more difficult” section of the wall on the other side of the road.

Pat pauses for a breather on the way down.

The hand rails were well used.

Negotiating the steps.

Without the tourist industry, the wall might have vanished entirely.

Several important sections, including the Bādálǐng section we were visiting, have been rebuilt, kitted out with souvenir shops, restaurants, toboggan rides and cable cars, populated with squads of unspeakably annoying hawkers and opened to the public (Lonely Planet).

The wall here was first built during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), and heavily restored in both the 1950s and the 1980s.Punctuated with dílóu (watchtowers), the 6m-wide masonry is clad in brick, typical of Ming engineering.

I am fairly sure that this section of the wall (the first part of the “difficult” side of the Bādálǐng renovation) features in the movie Mao’s Last Dancer.

Looking back on the “difficult” section we have just climbed, up to the top watch tower, and a bit beyond..

Part of the “more difficult” side.

A red-capped group prepares to walk up the “difficult” side.

Holding the flag.

The wall is climbed by old and young (as well as those in the middle).

Patterns

Black and white and shades of grey; Living and non living; Natural and man-made; Centuries old and this season; Free form and regular; Near and far.

Large Nian Carriage, for the use of emperors and empresses in the Qin and Han dynasties, to be drawn by eight horses.

Some of our more athletic tour group members coming down the “more difficult” side.

Detail from picture above.

Workers at the base of our section of the wall sifting sand by hand.

By the time we left, the weather had cleared and there were many more tourists. What an amazing day!

No comments:

Post a Comment